There has been talk in recent months about the narrowing yield curve and how this warns of a coming recession, normally accompanied by a graph of the 10-year/2-year Treasury spread which fell to 0.22% at the end of August 2018.

I have always used the 10-year minus the 3-month Treasury spread to indicate the slope of the yield curve but, although this shows a higher spread of 0.71%, both warn that the yield curve is flattening.

Is this cause for alarm?

First of all, what is the yield curve? It is the plot of yields on Treasuries against their maturities. Long maturity bonds normally have higher yields than short-term bills, to compensate for the increased risk (primarily of interest rate changes). If you tie your money up for longer, you expect a higher return. That is a rising yield curve.

A steep yield curve is a major source of profit to banks as their funding is mostly short-term while they charge long-term rates to borrowers, pocketing the interest spread.

The Fed sometimes intervenes in the market, however, restricting the flow of money to the economy, to curb inflation. Short-term rates then rise faster than long-term rates and the yield curve may invert — referred to as a negative yield curve.

At present we are witnessing a flattening yield curve, as short-term rates rise close to long-term rates.

A recent paper from Michael D. Bauer and Thomas M. Mertens at the San Francisco Fed concludes that a narrow yield differential has zero predictive ability of future recessions:

In light of the evidence on its predictive power for recessions, the recent evolution of the yield curve suggests that recession risk might be rising. Still, the flattening yield curve provides no sign of an impending recession. First, the evidence suggests that recession predictions based on the yield curve require an inversion (Bauer and Mertens 2018); no matter which term spread is used to measure its shape, the yield curve is not yet inverted. Second, the most reliable summary measure of the shape of the yield curve, the ten-year–three-month spread, is nearly 1 percentage point away from an inversion.

I was pleased to see that Bauer and Mehrtens find the 10-year/3-month Treasury spread more reliable than other spreads in predicting a recession within 12 months, with 89% predictive accuracy. They also refer to another study that came to a similar conclusion:

Engstrom and Sharpe found that their short-term spread statistically dominated the 10y–2y spread, and our findings are consistent with this result.

But both studies conclude that a negative yield curve (when the yield differential is below zero) is a reliable predictor of recessions. And Bauer and Mehrtens observe that, while the 10 year/2 year spread is less accurate, it is still a reliable predictor.

Are we just 22 basis points away from a recession warning? Let’s weigh up the evidence.

First, a negative yield curve is a reliable predictor of recessions. In the last 60 years, every time the 10-year/3-month spread has crossed below zero, a recession has followed within 12 months. There is one arguable exception. In 1966 the yield differential crossed below zero, the S&P 500 fell 22% and the NBER declared a recession, but they (the NBER) later changed their mind and airbrushed it out of history.

Second, while there is strong correlation between the yield curve and recessions, the exact relationship is unclear.

The most convincing explanation is that bank interest margins are squeezed when the yield curve inverts. When it is no longer profitable for banks to borrow short and lend long, they restrict the flow of new credit. Credit is the lifeblood of the economy and activity slows.

That was clearly the case in the lead up to the 2008 crash, but why are net interest margins of major US banks now widening?

The flow of credit also slowed markedly before the 1990/1991 recession but did not ahead of the last two recessions.

And growth in the broad money supply — zero maturity money (MZM) plus time deposits — accelerated ahead of the Dotcom crash and 2008 banking crisis.

Third, consider the Wicksell spread. Swedish economist Knut Wicksell argued in his 1898 work Interest and Prices that the economy expands when return on capital is higher than the cost of capital, with new investment funded by credit, and it contracts when the expected return on capital is below the cost of capital.

I was first introduced to Wicksell by Niels Jensen, who uses the Baa corporate bond yield as a proxy for the cost of capital and nominal GDP growth for the return on capital. Neils argues that the economy is near equilibrium when the Wicksell spread is about 2.0% — when return on capital is 2.0% higher than the cost of capital.

The above graph shows that 1960 to 1980 was clearly expansionary, with nominal GDP growth exceeding the cost of capital (Baa corporate bond yield). But the last almost four decades were the opposite, with the cost of capital mostly higher than the return on capital. Only recently has this reversed, suggesting a new expansionary phase.

One could argue that low-grade investment bond yields are a poor proxy for the cost of capital, with rising access to equity markets in recent decades. Also that nominal GDP growth rate is a poor proxy for return on capital. If we take the S&P 500, the traditional method of calculating cost of equity is the current dividend yield (1.8%) plus the dividend growth rate (8.0%), giving a 9.8% cost of capital. If we take the current S&P 500 earnings yield of 4.0% (the inverse of the P/E ratio) plus the earnings growth rate of 15.1% as the return on capital (19.1%), it far exceeds the cost of capital. You can understand why growth is soaring.

New capital formation is starting to recover.

Fourth, Fed actions over the last decade have distorted the yield curve. More than $3.5 trillion of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) were purchased as part of the Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) strategy, to drive down long-term interest rates. In 2011 to 2012, the Fed also implemented Operation Twist — buying longer-term Treasuries while simultaneously selling shorter-dated issues it already held — to further bring down long-term interest rates. Long-term rates are still affected by this.

In addition, Fed efforts to shrink their balance sheet may further distort the yield curve. The Fed has indicated that it will not sell Treasuries that it holds but will not reinvest the full amount received from investments that mature. If we consider that short-term Treasuries are far more likely to mature, the result could be that the maturity profile of the Fed’s Treasury portfolio is getting longer — a further extension of Operation Twist by stealth.

Conclusion

A flat yield curve does not warn of a coming recession. A negative yield curve does. Both the 10-year/2-year and 10-year/3-month Treasury spreads are reliable predictors of a recession within 12 months, but the 10-year/3-month spread is more accurate.

The correlation between the yield curve and recessions is strong but the actual relationship between the two is more obscure. Links between the yield curve, bank net interest margins, bank credit growth and broad money supply growth are more tenuous, with lower correlation.

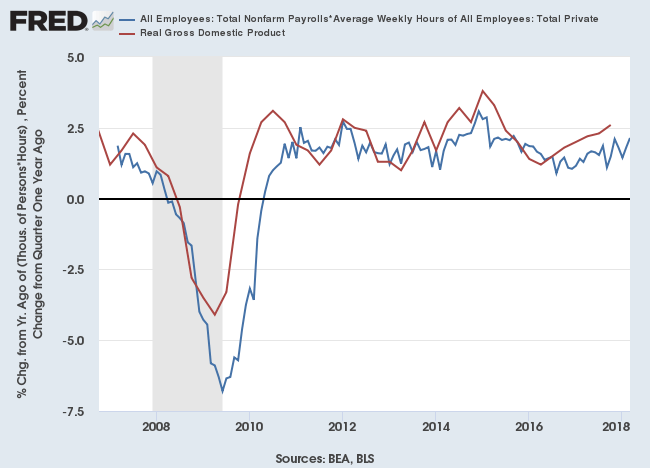

Also, return on capital is rising while cost of capital remains low, fueling strong capital formation. The economy is starting to grow.

Fed actions, through QE, Operation Twist, and even possibly steps to unwind its balance sheet, have suppressed long-term interest rates and distorted the yield curve. While the yield curve is still an important indicator, we should be careful of taking its signals at face value without corroborating evidence.

Lastly, we also need to consider the psychological impact. If the market believes that a negative yield curve is followed by a recession, it most likely will be. Beliefs lead to actions, and actions influence outcomes.

Treat yield curve signals with a great deal of respect, and be very wary of how the market reacts, but don’t mindlessly follow its signals without corroboration. The economy may well be entering a new growth spurt, with all its inherent dangers — and rewards.

I contend that financial markets never reflect the underlying reality accurately; they always distort it in some way or another and the distortions find expression in market prices. Those distortions can, occasionally, find ways to affect the fundamentals that market prices are supposed to reflect.

~ George Soros