In Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland a young Alice experiences a series of bizarre adventures after falling down a rabbit hole. The new Fed Chairman Jerome Powell will similarly have to lead global financial markets through a series of bizarre, unprecedented experiences.

Down the Rabbit Hole

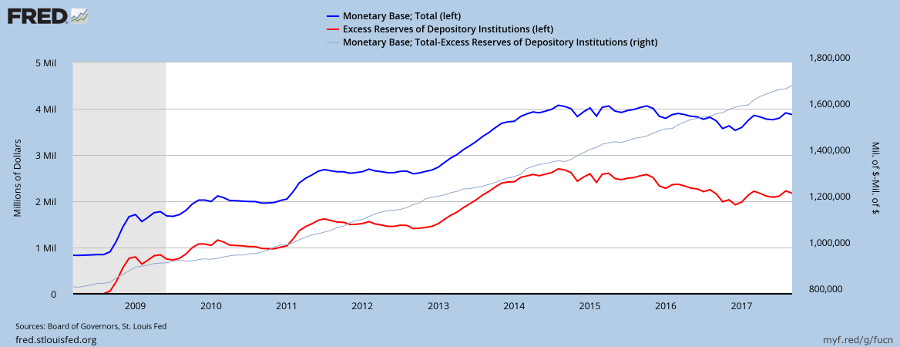

In 2008, after the collapse of Lehman Bros, financial markets were in complete disarray and in danger of imploding. The Fed, under chairman Ben Bernanke, embarked on an unprecedented (and unproven) rescue attempt — now known as quantitative easing or QE for short — injecting more than $3.5 trillion into the financial system through purchase of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

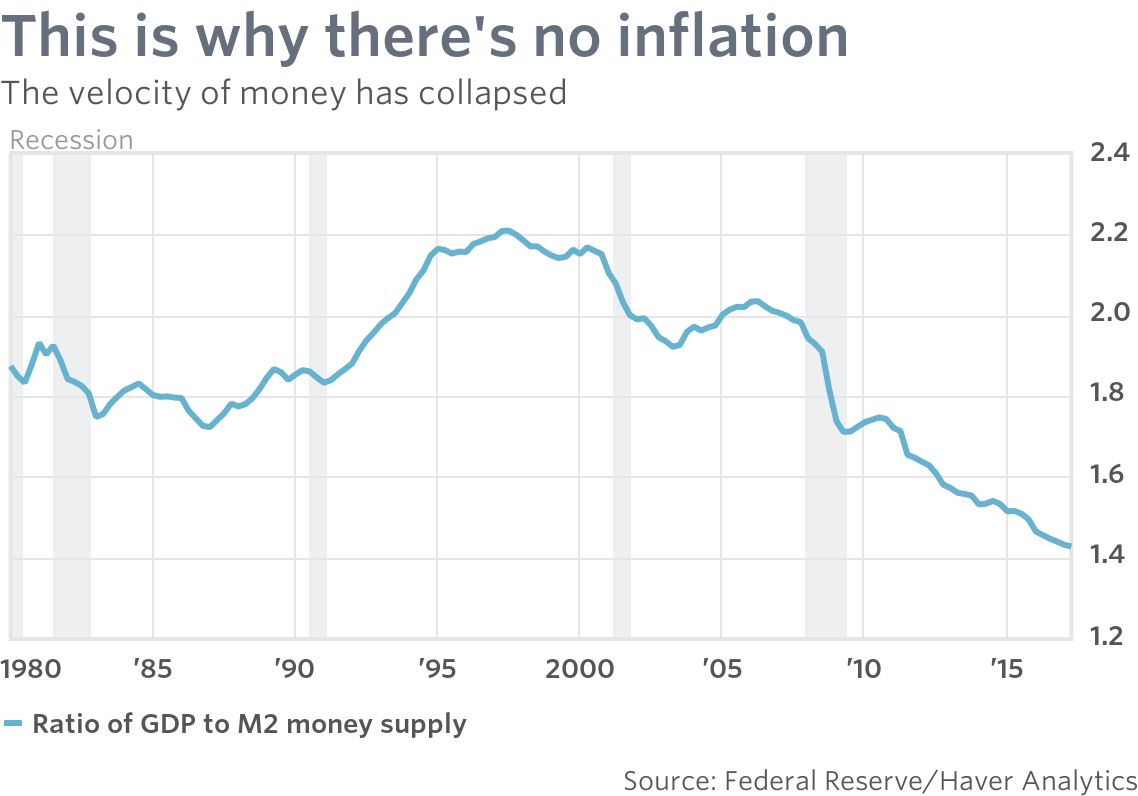

The Fed aimed to drive long-term interest rates down in the belief that this would encourage private sector borrowing and investment and revive the economy. Their efforts failed. Private sector borrowing did not revive. Most of the money injected ended up, unused by the private sector, as $2.5 trillion of excess commercial bank reserves on deposit at the Fed.

Richard Koo pointed out that the private sector will under normal cirumstances respond to lower interest rates with increased borrowing but during a financial crisis, when their balance sheets have been destroyed and their liabilities exceed their assets, their sole focus is to restore their balance sheet, using surplus cash flow to pay down debt. The only way to prevent a collapse is for the government to step in and plug the gap, borrowing surplus capital and investing this in infrastructure.

One Pill Makes you Larger

Fortunately Bernanke got the message.

… and spread the word.

And One Pill Makes you Small

Unfortunately, other central banks also followed the Fed’s earlier lead, injecting vast sums into the financial system through quantitative easing (QE).

Driving long-term yields to levels even Lewis Carroll would have struggled to imagine.

The Pool of Tears

Then in 2014, another twist in the tale. Long-term yields continued to fall in Europe and Japan, while US rates stabilised as Fed eased off on QE. A large differential appeared between US and European/Japanese rates (observable since 2014 on the above chart), causing a flood of money into the US, in pursuit of higher yields.

….. with an unwanted side-effect. The Dollar strengthened. Capital inflows caused the trade-weighted value of the US Dollar to spike upwards beween 2014 and 2016, damaging US export industries and local manufacturers facing competition from foreign imports.

The Mad Hatter’s Tea Party

A jobless recovery in manufacturing and low wage growth in turn led to the election of Donald Trump in 2016 promising increased protectionism against global competition.

Then in 2017, to the consternation of many, despite rising interest rates the US Dollar began to fall.

Learned analysis followed, ascribing the weakening Dollar to rising commodity prices and a recovery in emerging markets. But something doesn’t quite add up.

International bond investors are a pretty smart bunch. When they look at US bond markets, what do they see? The new Fed Chairman has inherited a massive headache.

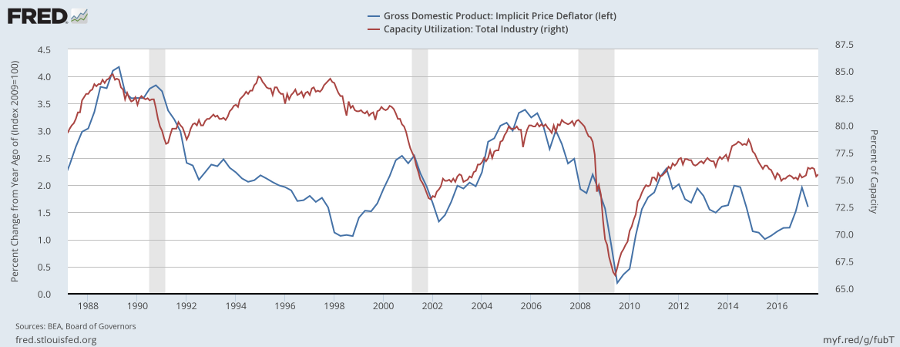

Donald Trump is determined to stimulate job growth through tax cuts and infrastructure spending. This will certainly create jobs. But when you stimulate an economy that is already at full employment you get inflation.

Who Stole the Tarts?

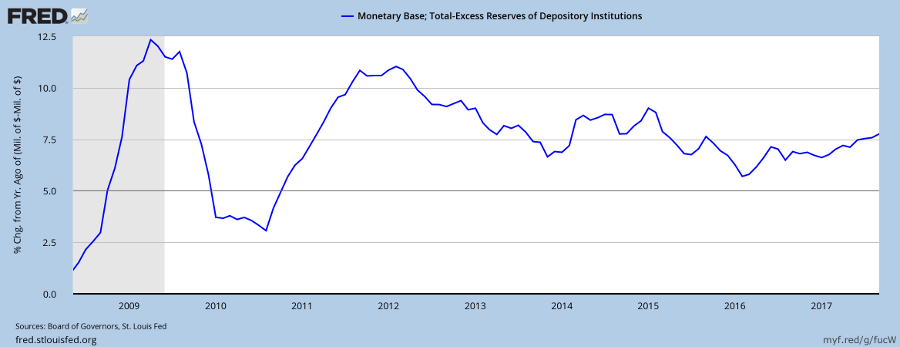

Jerome Powell is sitting on a powder keg. More than $2 trillion of excess reserves that commercial banks can withdraw without notice. Demand for bank credit is expected to rise as result of the Trump stimulus. Commercial banks, not known for their restraint, can make like Donkey Kong with their excess reserves provided by the Bernanke Fed.

Under Janet Yellen the Fed mapped out a program to withdraw excess reserves from the market by selling down Treasuries and MBS at the rate of $100 billion in 2018 and $200 billion each year thereafter. But at that rate it will take 10 years to remove the excess.

Bond markets are worried about what will happen to inflation in the mean time.

Off With His Head

The new Fed Chair has made all the right noises about being hawkish on inflation. But can he walk the talk? Especially with his $2 trillion headache.

….and the Red Queen, easily recognizable from Lewis Carroll’s tale, tweeting “off with his head” if a hawkish Fed threatens to spoil the party.

One pill makes you larger

And one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you

Don’t do anything at all

Go ask Alice

When she’s ten feet tall

….When the men on the chessboard

Get up and tell you where to go

And you’ve just had some kind of mushroom

And your mind is moving low….

When logic and proportion

Have fallen sloppy dead

And the White Knight is talking backwards

And the Red Queen’s off with her head

Remember what the dormouse said

Feed your head

Feed your head

~ White Rabbit by Grace Slick from Jefferson Airplane (1967)

Colin Twiggs is a former investment banker with almost 40 years of experience in financial markets. He co-founded Incredible Charts and writes the popular Trading Diary and Patient Investor newsletters.

Using a top-down approach, Colin identifies key macro trends in the global economy before evaluating selected opportunities using a combination of fundamental and technical analysis.

Focusing on interest rates and financial market liquidity as primary drivers of the economic cycle, he warned of the 2008/2009 and 2020 bear markets well ahead of actual events.

He founded PVT Capital (AFSL No. 546090) in May 2023, which offers investment strategy and advice to wholesale clients.