Growth in value of exports from China has slowed to single figures since 2012. It will be difficult sustain current GDP growth if this trend continues.

The Harper Petersen index of shipping rates for container vessels, the Harpex, remains near its 2010 low, reflecting continued weakness in Asian manufactured goods exports (a rise in exports from Europe or North America would be absorbed by the high percentage of containers returned empty to Asia on the round trip).

Rising Australian bulk commodity exports reflect the disconnect between Chinese imports and exports, with vast investment in infrastructure and rising stockpiles of raw materials used to sustain economic growth. But diminishing marginal returns on further infrastructure and housing investment mean failed recovery of manufactured goods exports would lead to a hard landing.

A key factor will be the strength of the RMB against the US Dollar. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard suggests that China will meet strong resistance in its attempts to export its deflation to the West. Treasury’s forex report to Congress (April 2014) highlight’s sensitivity toward further exchange rate manipulation:

In China, the RMB appreciated during 2013 on a trade-weighted basis, but not as fast or by as much as is needed, and large-scale intervention resumed. The RMB appreciated by 2.9 percent

against the dollar in 2013. However, as a result of the depreciation of the yen and many emerging market currencies, the RMB strengthened more on a trade-weighted basis, with the RMB’s nominal and real effective exchange rates rising 7.2 and 7.9 percent, respectively. For most of 2013 the RMB exchange rate was at, or very near, the most appreciated edge of the daily trading band, suggesting continuous pressure for greater RMB appreciation. During 2014, however, the exchange rate has reversed direction, depreciating by a marked 2.68 percent year to date.

There are a number of continuing signs that the exchange rate adjustment process remains incomplete and the currency has further to appreciate before reaching its equilibrium value. China continues to generate large current account surpluses and attracts large net inflows of foreign direct investment; China’s current account surplus plus inward foreign direct investment in 2013 exceeded $446 billion. The reduction in the current account surplus as a share of China’s GDP has largely been the reflection of the unsustainably rapid pace of investment growth. Finally, China has continued to see rapid productivity growth, which suggests that continuing appreciation is necessary over time to prevent the exchange rate from becoming more undervalued. All of these factors indicate a RMB exchange rate that remains significantly undervalued. Further exchange rate appreciation would help to smoothly rebalance the Chinese economy away from investment toward consumption.

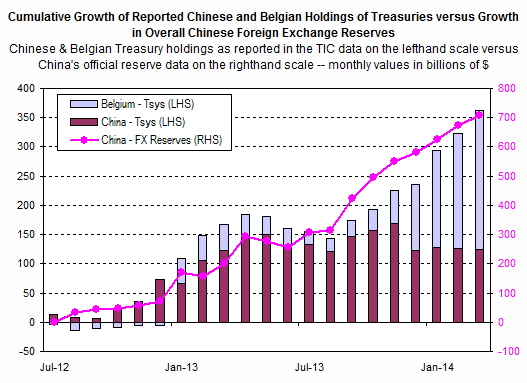

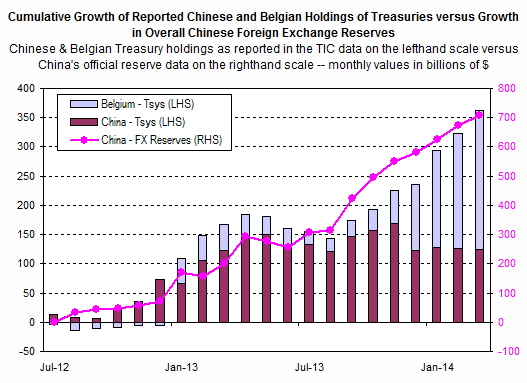

The Chinese authorities have been unwilling to allow an appreciation large enough to bring the currency to market equilibrium, opting instead for a gradual adjustment which has now been partially reversed . The expectation that the RMB would continue to appreciate over time resulted in large and increasing capital inflows in 2013. The PBOC’s policy of gradual adjustment triggered expectations of continued appreciation, and resulted in large-scale foreign exchange intervention. China’s foreign exchange reserves increased sharply in 2013, by $509.7 billion, which was a record for a single year. China has continued large-scale purchases of foreign exchange in the first quarter of this year, despite having accumulated $3.8 trillion in reserves, which are excessive by any measure. This suggests continued actions to impede market determination.

In short, China has been buying US Treasurys as a form of vendor financing, allowing them to export to the US while preventing the RMB from appreciating to its natural, market-clearing level against the Dollar. The fact that they are attempting to disguise this manipulation, using third parties, means that Congress is unlikely to tolerate further suppression of the RMB against the Dollar and will be forced to take action.

Feared sales of US Treasury investments by China, leading to a collapse of the Dollar, are most unlikely and would be a death knell for Chinese exports. Reversal of capital flows would cause rapid appreciation of the RMB against the Dollar, up-ending China’s former competitive advantage and boosting US exports.

Even without a reduction of existing Treasury holdings, appreciation of the RMB against the Dollar and Euro appears inevitable. This would be disastrous for China, causing them to forfeit their competitive advantage in export markets. And without access to the level of technology and global branding enjoyed by their Western counterparts, Chinese exporters are likely to struggle to hold existing markets, let alone achieve further growth. With diminishing returns on infrastructure and housing investment, China could soon run out of options to stimulate its economy. And its path as a global economic powerhouse may well follow that of its predecessor, Japan.