Great post on Twitter from Naufal Sanaullah depicting US sectoral balances using UK economist Wynne Godley’s analytical framework.

The key to understanding Godley’s analysis is that the sum of the four sectors is always zero. If one sector runs a deficit, it must be funded by a surplus in another sector — and vice versa. For example, if the government runs a deficit (i.e. spends more than it collects by way of taxes) it must borrow the shortfall from another sector — either the private sector (business or households) or foreign investors.

The federal government has run consistent deficits since 1970, apart from a short interval during the Dotcom era. Deficits were expanded massively during the GFC (2008 global financial crisis) to rescue the economy from a contraction in aggregate demand which, if left un-checked, would have resulted in a deflationary spiral on a scale similar to the 1930s. The government deficit was funded by private (household) saving until the early 1980s. Thereafter, household savings shrunk, gradually replaced by foreign investment. More on this later.

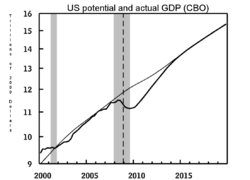

The business sector oscillated between deficit (i.e. borrowing more than they earn) and surplus until a massive investment splurge during the Dotcom era. Deficits by the business sector are not a real cause for concern, provided that borrowed funds are used to make productive investments. Unfortunately that was not always the case in the Dotcom era. Of far greater concern was the large surpluses run during the GFC, when the private sector stopped investing and used savings to repay debt. That is the major reason for the output gap (or GDP gap as it is sometimes called) and slow recovery depicted below.

One of the positives to come out of the GFC has been the resumption of household savings — a healthy sign in the economy if not carried to excess. But there are two glaring negatives.

First, the Federal government has been racking up public debt, kicking the can down the road since the 1970s with little effort to address the imbalance. When private sector savings dwindled in the 1980s, a new player appeared. Fiscal deficits were increasingly funded by foreign capital inflows, allowing government to deliver benefits in excess of taxes collected — like the sugar-plum fairy — without taxpayers being aware that the debt millstone around their necks was rapidly growing. Apart from a brief Clinton-era surplus, during the private sector Dotcom splurge, this has been going on for more than four decades — and is unlikely to change until Americans fix their political system.

A second threat is foreign capital inflows, shown in purple on the graph, which commenced in earnest with Japanese purchases of US Treasuries in the 1980s but reached a ‘nuclear’ scale when China joined the party in the early 2000s. While it may appear fairly benign, with foreign investors stepping in to lend Uncle Sam a helping hand, the damage is insidious. Foreign capital inflows are a major cause of the dwindling household surplus. Far from a friendly loan, these capital inflows were intended to undermine the competitiveness of US manufacturers in both domestic and export markets through currency manipulation.

To understand how currency manipulation works, we need to examine the foreign surplus in more detail. There are two parts to currency flows between nations: the current (income) account and the capital account. The current account comprises the trade surplus or deficit (the net sum of all trade flows between the two nations) and the smaller net income flow from investments.

The capital account reflects all capital flows, whether investment or loans, between the two countries. Again, the sum of the two is always zero. If there is a deficit on the current account (money flowing out), there must be a surplus on the capital account (loans and investments flowing in) to restore the balance. If not, and Japan/China had to increase their exports to the US without a reciprocal flow of capital, the value of the dollar would plummet against the yen/yuan until the trade balance was restored.

Think of it this way. If an importer in the US buys goods from China, they must purchase yuan to pay for the goods. If there are more imports than exports, the demand for yuan will be higher than demand for dollars; so the yuan will rise against the dollar until demand matches supply. But what currency manipulators do is invest money via capital account (mainly in US Treasuries), purchasing dollars to soak up the shortfall so that their currency doesn’t appreciate despite the massive trade surplus with the US.

The impact of this is two-fold. First US manufacturers shed jobs as they lose market share in both domestic and export markets. That cuts into the household surplus as unemployment rises and real wages fall. Second, the US government runs bigger deficits to make up for the demand shortfall in order to buoy economic growth. The end result is that US taxpayers grow poorer — as the size of the public debt millstone increases — while currency manipulators grow richer. The debt binge that led to the GFC was largely fueled by foreign capital inflows. The fact that this imbalance has been allowed to continue is a damning indictment of political leadership in Washington. There is no way that they can be unaware of the damage being caused to US manufacturers, households and to public finances. Change is long overdue.